Rewilding’s Human Cost: Who Gets Left Behind When Nature Takes Over?

As rewilding reshapes our landscapes, are we overlooking the people who have long cared for them?

I hesitate to write this.

I have hesitated for quite some time, circling the topic like a nervous border collie eyeing a particularly stubborn flock. Not because I don’t have thoughts - oh, I have thoughts - but because I know how these conversations go.

I’m a Director of Nature Recovery at a Wildlife Trust. On paper, I should love rewilding. I don’t. At least, not in the way I’m expected to. I have complex, messy, muddled, deeply nuanced, strong feelings about rewilding - strong enough that they tend to escape my brain at inconvenient moments and they come out tangled and tripping over each other.

The worst thing about rewilding isn’t rewilding itself - it’s the way the conversation around it has become so polarised, so militant at times, that questioning it feels like stepping into a badger sett while wearing a sign that says Please Bite Me.

If you critique rewilding, you risk being labelled anti-nature, a defender of outdated farming practices, traditional (always said with a sneer), or worse, part of the problem. But the problem with militant ideologies is that they leave no room for complexity, for contradictions, for the kind of thoughtful, compassionate, curious, open debate that good land stewardship demands.

And so, here I am. Writing about it.

Because if we care about the future of our landscapes - our living, working landscapes - we need to be able to talk about rewilding’s tensions, its unintended consequences, and the uncomfortable fact that in some cases, it’s being used as a means of exclusion and displacement.

And I, for one, have no interest in being part of a movement that sees people as obstacles rather than allies.

What do we mean by Rewilding?

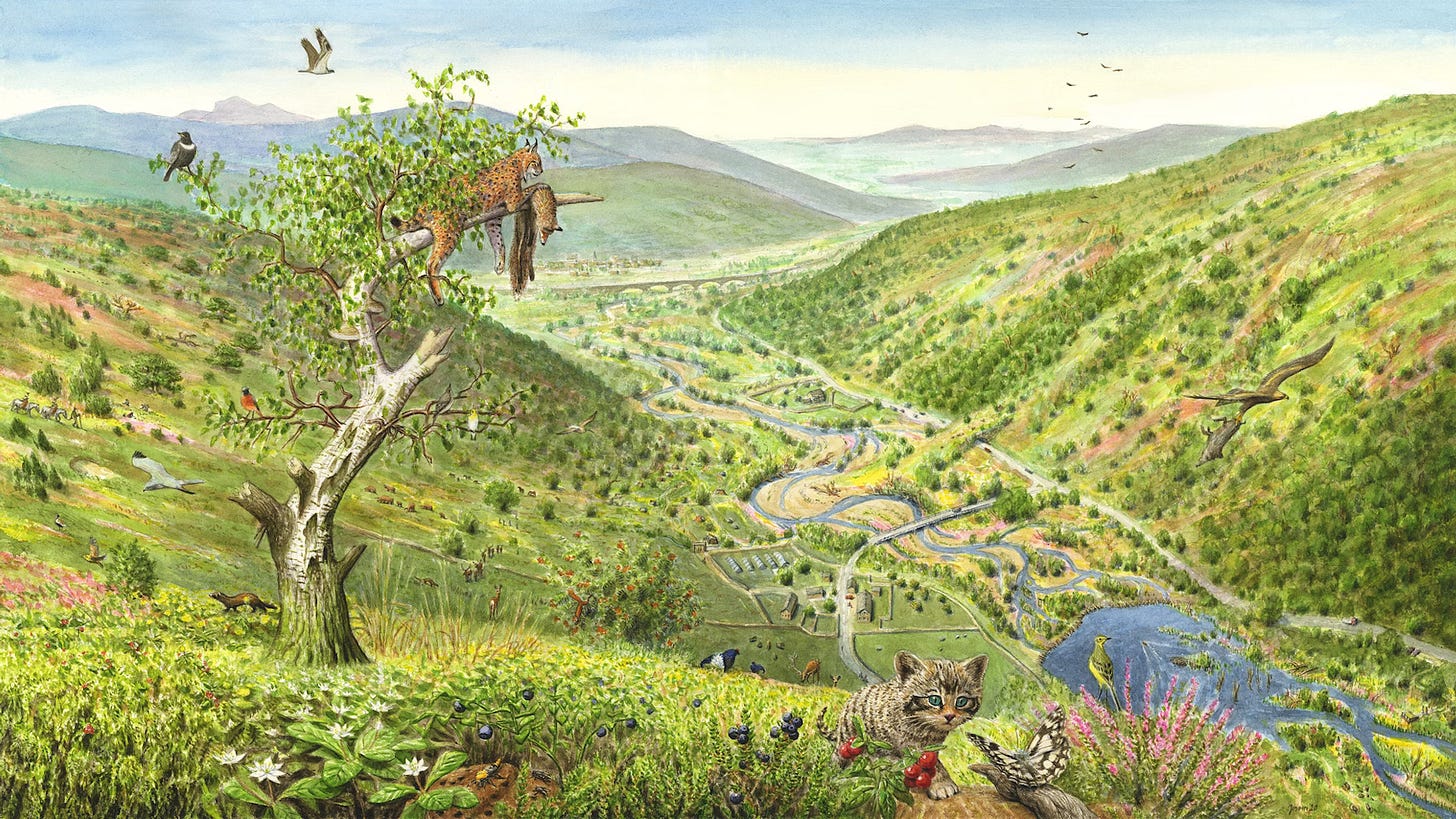

Rewilding is often described as restoring ecosystems by allowing natural processes to take over - removing intensive farming, reintroducing lost species, and letting landscapes return to a ‘wilder’ state.

But definitions, like landscapes, are never as fixed as they seem. To some, rewilding is a grand letting go and letting nature do the work. To others, it involves active intervention, such as reintroducing herbivores and predators to reshape the land. It can also be a mix of both.

Beneath the optimism, though, there is something else, a quiet but growing discomfort. In rural communities, rewilding often feels like something done to people rather than done with them.

And this is where the tension lies - not in the idea of nature recovery itself, but in the way that rewilding is framed, funded, and implemented.

The Rewilding Boom and Rural Anxiety

It is easy to be seduced by the sweeping narrative of land sparing - which is taking farms out of production and returning them to the wild - of imagining England as it might have been before ploughs and fences and neatly divided fields. In some cases, this has worked beautifully. Birds return. Insects hum in the long grass. The land, given time and space, remembers itself.

But there are other stories, too. Stories of tenant farmers who have lost their homes and businesses to rewilding schemes. Of villages where the last dairy herd has vanished, replaced by a vision of ‘wildness’ that leaves no room for those who once shaped it. Of food systems quietly uprooted in the name of progress. Because when land is rewilded without considering those who have long worked it, something more than pasture is lost.

And yet, the dominant rewilding narrative rarely acknowledges this loss. There is no obituary for the displaced farmer, no headline for the severed connection between people and place.

Rewilding or Rural Gentrification?

Some rewilding projects feel uncomfortably like rural gentrification. Wealthy landowners, NGOs, and corporate investors move in with ambitious plans for nature restoration, while the farmers and the communities who once worked, lived, and loved the land find themselves pushed out.

Take for example, ‘The Millionaire Rewilding the countryside, one farm at a time.’ It was met with hundreds of comments, but one in particular stood out:

“I find it shocking that the media holds these up as such beacons of hope and somehow ignore that these projects only happen because their founders are incredibly wealthy and don’t have to worry, as every farmer does, every single day about simply making a living from their land. It would appear that food security, the rural economy, heritage and history are not worth bothering ourselves with in the mad rush for solutions.”

This frustration is understandable. For those who rely on the land for their livelihoods, it’s galling to see deep-pocketed investors swoop in and be hailed as heroes.

But the problem runs deeper than rewilding itself, exposing a much older issue: who owns Britain’s land and who has a say in its future?

"Land ownership in Britain remains among the most inequitable in the world... While a tiny, unrepresentative class monopolises rural Britain, the rest of us are treated as trespassers in our own nation." - George Monbiot, The Guardian

Monbiot is right that Britain’s land ownership system is deeply flawed and his argument flips the usual narrative. What if rewilding isn’t causing exclusion, but merely exposing an already broken system?

Who Gets to Decide the Future of Our Land?

The real tension isn’t between rewilding and farming - it’s between competing visions of how land should be managed. Regardless of which side of the debate you’re on, whether you see land as something to be farmed or something to be given back to nature, one question remains:

Who gets to decide the future of our land?

It is an old question, older than this particular battle over rewilding, older than conservation itself. It stretches back through centuries of enclosures and evictions, land reforms and land grabs. The Highland Clearances come to mind, where entire communities were forced from their homes, their villages burned, their land repurposed for sheep farming and, later, sporting estates.

If history tells us anything, it’s that land has rarely been decided by the people who live and work on it. The shape of the countryside has always been shaped by power.

And power has never been equally shared.

For centuries, the decisions shaping Britain’s countryside have been made from above. By monarchs parcelling out vast estates, by landowners fencing off commons, by policymakers in Whitehall drafting agricultural reforms with little input from those who would feel their impact most.

Today, it is billionaires buying estates for carbon credits. Charities acquiring land for conservation. Politicians shaping agricultural policy from Whitehall. The faces change. The pattern remains.

So when we ask, ‘Who gets to decide the future of the land?’ we’re not just talking about rewilding vs. farming. We’re talking about power - who holds it, who wields it, and who is left out of the conversation.

And power, more often than not, is enforced through language.

Rewilding’s Language: Correction, not Collaboration

The language of rewilding can feel less like an invitation and more like an accusation. You were doing it wrong. Now let us show you how it should be done. It is not framed as collaboration, but correction, as if biodiversity were a switch that could be flicked back on if only we cleared away the human clutter.

This mindset creates a false war, dividing the world into neat, opposing forces. Nature versus farming. Progress versus tradition. Those who see the big picture versus those who are clinging to the past.

There is a deep and maddening irony here. If rewilding worked with farmers rather than around them, the possibilities would be vast. A landscape that is both productive and teeming with life, where nature and people coexist, where farming is not seen as the villain but as part of the fabric of ecological recovery.

Because nature recovery isn’t a choice between wild landscapes and working ones. It isn’t a battle between two sides, a war where one vision must triumph over the other. It is a question of how we live alongside nature, how we acknowledge history without being bound by it, and how we build a future where people and the land can thrive together.

Rewilding Has Burned Bridges - Is It Willing to Rebuild Them?

If rewilding is to be more than an elite movement, more than a rebranding of conservation for the modern age, it must reckon with its human impact. If rewilding truly wants to be about restoring nature, then it needs to start by restoring relationships, too.

But I find myself wondering - is it too late?

The damage has already been done in so many places. Farmers have lost their land, their homes, their livelihoods. Rural communities have been changed, perhaps arguably for the better in some ways, but for the worse in others. Yet in its eagerness to reclaim the past, rewilding has created new wounds - wounds that won’t be healed by glossy websites or carefully worded community consultations.

For many farmers, rewilding has become synonymous with loss. Loss of land. Loss of purpose. Loss of agency.

As one Welsh farmer put it:

“It’s not rewilding, it’s land grabbing. How can you say you’re restoring nature when you’re wiping out farming communities to do it?”

Another, speaking at a meeting about land use changes in the uplands, was more blunt:

"They say 'rewilding' and what they mean is 'getting rid of us.'”

And the hardest thing, the thing I hesitate to even admit, is that I’m not sure rewilding as a movement wants to come back from these mistakes.

Because to do so would mean acknowledging them in the first place. It would mean admitting that some of the grandest, most celebrated projects - the ones that have drawn headlines, investment, and high-profile endorsements - were not as cleanly executed as the press releases suggest. It would mean sitting down with the people who were told they had no place in the future of these landscapes and saying, We got it wrong. How do we fix this?

The Hardest Truth of All

And here’s where it gets even more uncomfortable.

Because this isn’t just their mistake, whoever they might be. It’s ours too.

That includes the Wildlife Trusts. My wonderful, well-meaning, beautiful Wildlife Trusts. (Who, I should add, also pay my bills, so if my boss or anyone from payroll is reading this - please know I say this with deep compassion, respect, and an urgent desire to remain employed.)

I wish it didn’t, but it does.

The uncomfortable truth is that my own organisation, and others like it, have been part of the problem. We have championed rewilding projects that have displaced farmers. We have contributed to narratives that, however unintentionally, cast those working the land as antagonists to nature. We have, at times, spoken about bringing nature back as if the people who have lived and worked in these landscapes for generations are nothing more than an inconvenient footnote in our story.

I don’t say this lightly. I believe in the work we do. I believe in restoring nature, in creating habitats, in reintroducing species that belong here. But I also believe in honesty. And if we truly want to get this right, we need to own up to where we’ve gone wrong.

The Work Ahead

And now, as a result, we have a lot more work to do. A lot of old narratives to unpick, first impressions to rewrite, and deep-seated preconceptions to unravel. Trust to rebuild. Bridges to repair.

If we’re serious about nature recovery, we have to stop seeing farmers as outsiders to the cause and start seeing them as the key to unlocking it. Because they are.

We can continue as we are, telling ourselves that rewilding is inherently good while ignoring those it has left behind. We can press forward, sure of our righteousness, brushing aside the farmers, smallholders, and rural communities who feel like collateral damage in the race to restore nature.

Or we can choose differently.

Nature Recovery Needs Farmers

The future of nature recovery cannot be built on the foundation of exclusion.

And that means meeting people where they are, walking side by side with them, and having honest conversations about food production, livelihoods, and what kind of countryside we want to create.

And I mean not just talking at them, but working with them - helping to navigate change together, even when the message is painful. Because the truth is, farming does need to evolve. But that evolution can’t be something done to people; it has to be something we build with them.

The future of nature recovery isn’t about choosing between wild landscapes and working ones. It’s about finding a way for them to thrive together.

What do you think?

Can rewilding repair its broken relationships and work alongside farmers? Or has too much damage already been done?

How do we move forward in a way that truly balances nature recovery with the needs of rural communities?

I’d love to hear your thoughts!

If you liked this post, please consider sharing it with friends, colleagues, or anyone who might find it interesting. You can also hit the 💚 button or leave a comment—I’d love to hear your thoughts!

Haven’t subscribed, but like what you’re reading?

Subscribe for more musings on nature recovery that land in your inbox each week.

I think there has to be space within the idea of rewinding for regenerative agriculture. Going back to the days of crop rotation, with natural hedgerow dividers, and maintained drainage ditches. Mono crops are ruining the soil, run off from intensive animal rearing is polluting the waterways. There has to be space to change those things, and still rewild. 💜😊

Carrie...thank you gor writing this piece! As a lifelong devotee to all sentient beings, most folk would assume im 100% behind rewilding but Ive had many reservations right from the get go. I absolutely want to live in a country (world) that has let nature recover. I also want to live in a country that has strong food systems and respect for where and how that food is produced. We need to eat, and despite being vegetatarian my whole life I respect for some that requires eating livestock. There has been a race to get food as cheap as possible, households spending a tiny proportion of income on food compared to the relatively recent past. Good food enables good health, and with our health system also in crisis it seems to me no one is joining the dots between any of these issues. So often Im drawn back to Robin Wall Kimmerer's Braiding Sweetgrass, humans have a role in the grand systems of life on this planet, we are part of the balance and there are many spinning plates to be kept from smashing.